A Treatise on the Use of Soap

The history of soap is intimately related to the history of water. In the 15th century, the soap industry developed significantly in the South of France, with the first proper soap factory inaugurated in Toulon in 1430. The adventure goes on in the reign of Louis XIV, who elaborates the rules for making Savon de Marseille, still in use today: no additives, no preservatives, and, above all, no perfume. The precious Grail is made of vegetal oil, olive residue (from the pressing of olive oil), and soda, which allows the oils to saponify.

At the time, though, water is considered full of potential illnesses, and people prefer to use perfume powder. It may conceal any unpleasant smell, but it doesn’t kill germs. Soap is reduced to its domestic use – laundry – and baths are demonized: when the plague strikes Marseille in 1347, people are keen to believe that warm water opens up skin pores and thus facilitates contamination. Finally, the 18th sees the ablution come back into fashion: this intimate moment is particularly appreciated in libertine circles. English Water Closets and bidets come into use, and can be seen depicted by masters of classical painting like Boucher or Eisen.

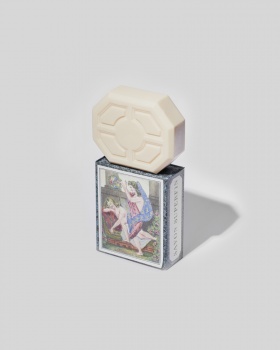

Once a novelty in wealthy homes, soap became more widespread in the 19th century, before the concept of “public hygiene” emerged. The Hygiene Council, embracing Pasteur’s discoveries, launches several public campaigns and recommends the sterilization of baby bottles, brushing of teeth or vaccination. Needless to say, soap rubs its hands in glee: with the industrial revolution, its yearly output amounts to more than 12 500 tons. In Marseille, soap factories diversify their methods and use both local olive oil and palm or copra oil imported from the colonies. Soap brands multiply, and perfume makers such as Gellé Frères and Jean-Vincent Bully become masters of toilet soaps.

To sum up the history of cosmetics: it is possible to be clean and beautiful.

By Mathilde Berthier

laissez un commentaire

Connectez-vous pour poster des commentaires